I’m continuing with the theme of cool activities with my excellent colleagues in Granada, in addition to our classics like playing board games and going out to eat together in good restaurants.

The time before last, I suggested a coding game.

On the advice of my friend @riduidel/Nicolas Delsaux, and because I’m not familiar with this sort of thing, I chose the extreme carpaccio game.

You can find all the details here:

https://github.com/dlresende/extreme-carpaccio

I’d encourage you to read the description of the game, at least from the players’ point of view, if you intend to play it. When I say ‘play’, yes, it sounds like a kind of TTRPG with code. It’s a fun, competitive game in which several teams compete by delivering code and trying to score points.

That day, five developers were present, plus the monitoring supervisor, the quality supervisor, a PO and the support supervisor. I asked them to get together in 4 groups (3 groups of two, one group of three), each containing at least one dev, the other being a ‘manager’. Each group represents a small IT company to which the Big Client (me) orders an e-commerce system.

The game is available on the github repo above and is very well done. The GM deploys a server that sends orders to the players’ systems. The players have to accept the commands, do a little calculation on them according to the specs and send back the result of the calculation. If they get it right, they score the amount of the order in points. If it’s wrong, they lose half the amount in points. If the answer is 404, no gain, no loss.

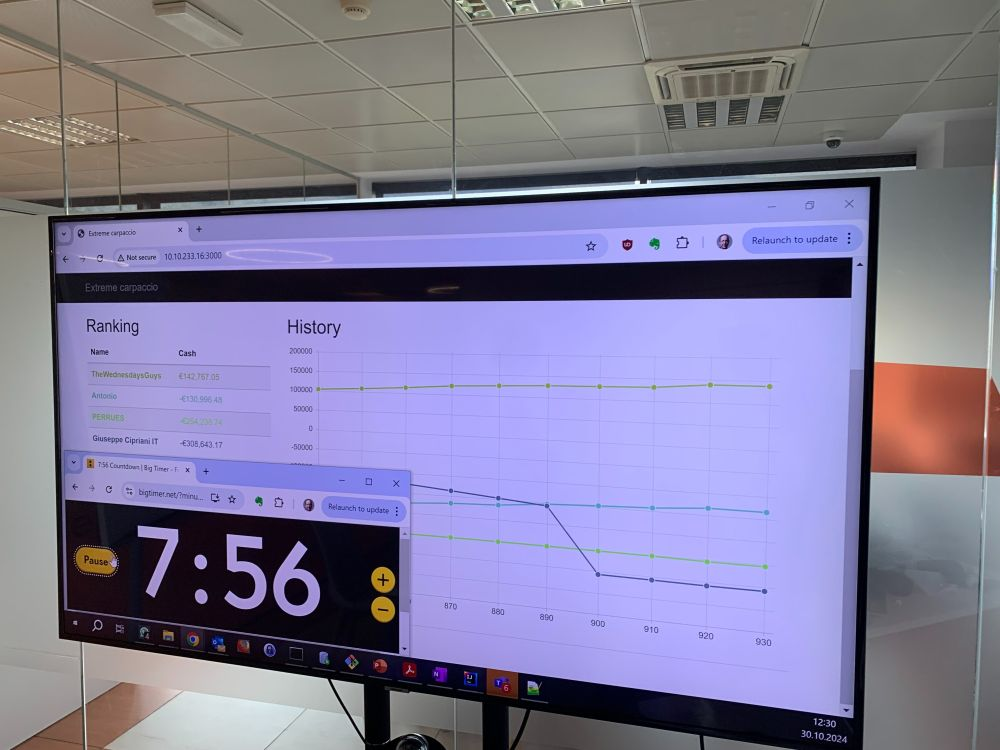

We were in a large room, reserved for two hours. With the result, in points, displayed on a big screen.

The game is very well prepared. If you’re planning to run it, allow one or two hours for preparation at home, just long enough to master the technical tools (the only thing I missed was knowing that a NodeJs app deploys by default on port 3000), plus half an hour at the game venue to test the network config (basically, deploy the server on one machine, the clients on another, play with ipConfig, and check that it’s working).

First thing’s first, it’s great fun. If you’re feeling a bit like a storyteller, this is for you. You can play characters, do big voices, bang on the table, wave your arms… And the players can play the smooth-talking manager who appeases the customer, make impossible promises and so on. It’s a great way to let off steam and have a good laugh. The screen that displays the points immediately shows whether it’s working or not. I’d set up 10-minute ‘sprints’, so that I could count the time in the game (‘at what sprint are you going to deliver in production?’), which isn’t included in the scenario.

All the teams delivered, delivered late and lost points before recovering them.

At the end, we spent around twenty minutes debriefing. Each team will learn its own lessons (ours are below, beware of spoilers).

I’d recommend this game, everyone had fun (devs and non-devs), we were really able to laugh about what sometimes makes us stressed and say things we wouldn’t have been able to say before.

SPOILERS

DON’T READ THIS BEFORE PLAYING THIS GAME

- The code to write is simple, the specs are clear

- but the stress, noise and pressure make many good practices go out the window

- the ‘manager’ of each team has more or less played the role of intermediary with the Big Client (the GM, who scolds and grumbles)

- obvious elements were ignored, resulting in lost points (return 404 when you don’t know where there is an error)

- experienced devs have made rookie mistakes

- no team wrote a single unit test. (some didn’t even realise that the proposed code skeleton contained tests) even though this is an established dev practice and the specs propose test data

- everyone was psychologically fooled by the big time counter on the screen without realising that the division into ‘sprints’ was purely artificial and didn’t correspond to anything real.

All this enabled us to see, outside the game, how the evolution of the open space (the team now works in a less quiet environment) and the more frequent interruptions linked to production (and to unplanned requests from management) have a major impact on quality and production, despite an increasingly experienced team.